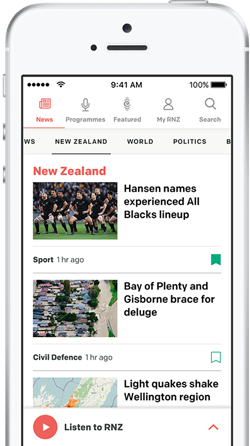

Peter Humphreys (left) with his daughter Sian, and Christine Fleming (right) with her son Justin Coote. Photo: NZ Herald / Sylvie Whinray

The Supreme Court has ruled two parents who care full-time for their disabled children are, in fact, employees of the government, and should receive the same benefits and protections.

Under the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000, family members who provided support services could receive payment for their care of their disabled family members.

Christine Fleming, who cares full-time for her disabled son Justin, and Peter Humphreys, who cares full-time for his disabled daughter Sian, had their case heard by the Supreme Court in April.

The decision was released on Tuesday, in favour of recognising both Fleming and Humphreys as ministry employees.

Jurisdiction for disability funding has transferred since court proceedings began from the Ministry of Health, to the Ministry of Social Development.

For carers not to be recognised as employees meant they weren't entitled to things like holiday pay and protection against unfair treatment - and during the April hearing, lawyers said the issue could potentially affect thousands of family carers.

Fleming's and Humphreys' individual cases had initially been won in the Employment Court, but were overturned by the Court of Appeal.

The Court of Appeal ruled Fleming wasn't a homeworker after she turned down the health ministry's offer of funding through a programme called Funded Family Care, which would only have funded her initially for 15.5 hours, and later, 22 hours, for what was actually round-the-clock care for Justin. She decided she was better off on a benefit.

The court ruled separately that Humphreys was classified as a homeworker during the six years he received Funded Family Care, which meant he was technically an employee of Sian - but when the funding scheme was replaced by a new one, called Individualised Funding, in 2020, his status changed and he was no longer considered an employee.

He argued in court nothing had changed for him, or for Sian, and it was unfair that his status as an employee had disappeared.

Today, the Supreme Court - in reasons laid out by justice Dame Ellen France - has reinstated both Fleming's and Humpheys' employee statuses.

It also ordered costs worth $50,000 to be paid by the Attorney-General to Humphreys, but left the working out of costs for Fleming to the Employment Court.

In making its decision, the court had to consider the definition of "work".

It found: "We consider the appellants are subject to constraints and responsibilities and that what they do is of benefit to the Ministry as their employer. They are working when caring for Justin and Sian, at least for some of that time."

It also had to consider the concept of "engagement" as an employee.

In Humphreys' case, it found he could still be considered "engaged" as a "homeworker" even though he had not been formally selected - that is, he was acting as caregiver without being hired to fill that role by the ministry.

In Fleming's case, the judgment noted that without his mother's care, the government would have had some obligations for Justin's care itself, adding weight to her status as a "homeworker".

While the Supreme Court left the matter of costs for Fleming to the Employment Court, for the purposes of "assist[ing] resolution by the parties" it noted, "it is accepted that Justin needs full-time care for the 24-hour period each day of the week.

"In these circumstances it is difficult to see, on application of the factors in Idea Services, how Ms Fleming would not be working a 40-hour week".

'Over the moon'

Humphreys, who watched the reading of the judgment on Tuesday afternoon via video link, told RNZ he was "over the moon" with the decision.

"It's been a long six years," he said.

"I don't really know where we go from here, other than we've got the same rights as other workers, and that's what we've been trying to do all the way through, really."

"[Family members] do the work the same as other [care] workers," he said.

For him, the fight began when he asked for government support to renovate their bathroom, to make it more accessible for Sian.

"They said there was just minimal support and you will have to be means-tested. My question was, I'm the employee, why should I have to provide a bathroom for my employer?"

The mixed messages continued when they lost the appeal, so to have a definitive answer from the Supreme Court had been a long time coming for the families.

"It feels like closure," Humphreys said.

Independent disability advocate Jane Carrigan, on behalf of Fleming, agreed.

"It's seven years, seven months since I filed for Christine in the Employment Court," she told RNZ on Tuesday.

"These issues have really been before the courts for the last two-plus decades. But this is the first time we've ended up in the Supreme Court, so we've finally got a decision the government aren't going to be able to ignore."

She said the decision could affect thousands of families - not just those of family members with disabilities, but aged care, health and mental health carers as well.

She confirmed Fleming would be seeking costs, but couldn't give details yet.

She said considering the Employment Court acknowledged that employment rights were human rights, she was hopeful for a good outcome there.

Ministry declines to comment

The Ministry of Health declined to comment, and Anne Shaw, deputy chief executive of disability support services at the Ministry for Social Development, said they would be carefully considering the court's decision.

"We would like to reassure the disabled people, their family, whānau and carers that existing care arrangements continue while this consideration takes place."

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.