By Liam Fox, ABC

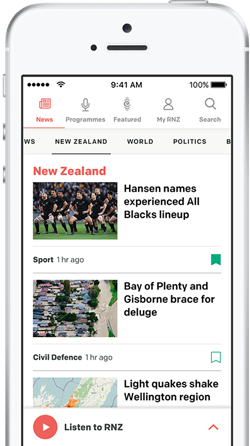

Fiji's Cloudbreak has some of the best waves in the world and hosted the 2025 WSL finals. Photo: ED SLOANE / WORLD SURF LEAGUE

- The Fijian government will repeal a law from 2010 that guaranteed free access to the country's surf breaks.

- While details are yet to be released, the government says a new law will "ensure resource owners are compensated for the use of their marine areas".

- The bill to revoke the surfing decree will go to parliament next week.

Surfers wanting to catch a wave in Fiji may soon have to pay for the privilege, as the government moves to repeal a unique law that opened up access to the country's world-class reef breaks for tourists and locals alike.

Foreign-owned resorts used to have exclusive access rights to famous waves like Cloudbreak, off Fiji's Tavarua Island, so you had to be a paying guest to ride them.

"We, as locals, couldn't surf," said Fiji surfing pioneer Ian Ravouvou Muller. "We were treated as second-class citizens in our own country and who would like a situation like that, where you can't even surf your own waves?"

In 2010, the military dictatorship in charge of the country at the time, led by former commander Frank Bainimarama, imposed a Surfing Decree, prohibiting exclusive access rights, so anyone could surf anywhere, without having to pay a fee or get a permit.

Even critics of the then-government acknowledge it helped turn Fiji into a premier surf-tourism location.

"It allowed us to start surfing," Muller said. "Ever since we opened, there's been an explosion of local surf businesses and local surfing.

"It's incredible. That's why we got all these young up-and-coming stars now, because they're able to surf some of the best waves in the world."

Indigenous Fijians left out

While some locals cashed in on the boom, the indigenous owners of the coastlines and seas where people were surfing could only look on as others profited.

The decree removed their rights to control access to their marine areas and banned other activities from surfing hotspots, like fishing.

"No-one was allowed to receive any compensation, so they were denied the huge opportunities to make something out of their resources," said Tourism Minister Bill Gavoka.

Fijian surfing pioneer Ian Ravouvou Muller. Photo: ABC / Supplied

Gavoka said a long-foreshadowed bill to revoke the surfing decree would go to parliament next week, but what exactly would replace it remained unclear.

"In place will be a structure that is designed to liberalise access to all the marine areas... and ensure resource owners are compensated for the use of their marine areas," Govoka said.

It is understood the replacement legislation is intended to restore indigenous rights over marine areas, rather than give back exclusive wave access to resorts.

Gavoka said it would undergo public consultation, after it was tabled in parliament.

How Indigenous owners would be compensated was yet to be determined, but Govoka said people could not set their own fees for access to waves.

"No, no-one will be charging anything that is out of line," he said.

Concern and confusion over what's next

The change and lack of concrete information about what comes next is causing some concern among stakeholders.

The Fiji Surfing Association and the Fiji Hotels and Tourism Association both declined to comment on the upcoming repeal of the surfing decree.

Both groups said they did not have enough information on the change and were waiting to see the new law when it reached parliament.

Meanwhile, Muller has a foot in both camps - having indigenous Fijian ancestry and running a surf-related business.

He said it was only fair traditional owners got a slice of the action.

"Our people haven't been fairly been compensated," he said. "That's been their fishing grounds.

"Surfers come in, they chase away the fish. They have no fish to eat - they need to be compensated.

"They destroy the reef - they need to be compensated."

When the public consultations began, Muller said he would propose the creation of what he called "ocean parks".

"Where it's user pays and that money goes back into lifeguards, security, village protection, reef protection, making sure that the ocean and the people are looked after, and it's sustainable," he said.

"I think that's probably the most sensible way of moving, where everybody wins and it could be a great model for the rest of the world."

- ABC