Rainbow Park Nurseries owner and general manager Andrew Tayler. Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

In the balmy greenhouses of Rainbow Park Nurseries, orchids bloom in perfect rows - a picture of calm that hides how close the operation came to crisis.

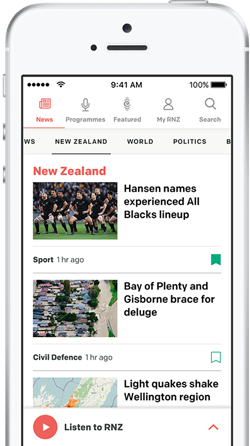

The South Auckland business - which grows houseplants and trees for major retailers - has just finished a $2.5 million project to get off natural gas. An army of industrial heat pumps now feed two giant hot-water tanks, keeping the glasshouses at up to 28°C through winter nights.

Manager Andrew Tayler is blunt: without public money, it would not have happened.

"We were very lucky we got the funding," Tayler says. "If we didn't, we probably would have thrown waste-oil burners on the front of the boilers and walked away."

Rainbow Park was one of the last companies to receive a major grant from the government Investment in Decarbonising Industry (GIDI) fund before new rounds were frozen and the scheme was branded "corporate welfare" by the coalition. EECA covered roughly a third of the cost - about $880,000 - with the nursery borrowing and doing much of the installation work itself.

With no local examples to learn from, the company relied heavily on the advice of suppliers and consultants - and a lot of hope.

"Bolting 32 heat pumps together and putting them into two enormous hot-water tanks… it was a leap of faith," Tayler says. "But if we hadn't, we'd still be in the cycle of sweating every year about the gas - are they going to supply us, what is the price going to be, how is that going to affect our business?"

A swathe of heat-pumps warm the water in the huge hot water tank at Rainbow Nurseries. The hot water is then pumped through pipes to warm the glasshouses. Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

Rainbow employs more than 90 people. Doubling gas prices, he says, would have "hamstrung" the business. Instead, the nursery now buys certified zero-carbon electricity and uses the savings on its gas bill to pay down the new system.

"We'd have to do what some other businesses are doing - curtailing production, turning the heat off in some compartments, maybe laying off staff, changing what we grow," Tayler says.

"I do feel like some of the guys that didn't have the opportunities we have will be finding it very tough."

Since Rainbow Park switched, the bottom has truly fallen out of New Zealand's gas market. Supplies are collapsing faster than expected. Long-term contracts have become scarce and expensive.

Factories that rely on gas now find themselves in a strange limbo - unable to secure long-term supply, facing steep price rises, but with little guidance or public funding to help them make massive, costly decisions about their energy future.

The result, energy experts and businesses warn, is a "forced transition": a messy, unmanaged exit from fossil fuels that risks shuttering plants, hollowing out regional economies and pushing up prices for everyone else.

"Energy transitions work better when people have time to see the signals and make informed decisions," says energy analyst Richard Hobbs, a partner at Boston Consulting group. "When shocks arrive unexpectedly and timeframes are short - that's when you get the really bumpy situations."

'We've been backed into a corner'

In Bay of Plenty, Whakatāne Growers heats four hectares of capsicum and chilli glasshouses with a mix of coal and gas. The plan had been to get off coal and move fully onto gas - cleaner and easier to run, with captured CO₂ helping lift yields by up to 20 percent.

Instead, site manager and co-owner Michael Simpson is stuck.

A year and a half ago, the company went to renew its gas contract. Their existing supplier could not even offer one. Two other offers came back - at 40-50 percent higher prices.

"There's two main issues," Simpson says. "Supply - it's never a good thing to not know how the future is going to look - and cost. Gas prices have just exploded, and no one's had the opportunity to make the best decisions for their business. You've got to rush now."

Whakatāne Growers still runs its gas boiler, but has had to dial back temperatures, focus on efficiency and lean harder on coal.

"We never really stopped using coal, but we didn't go any further with transitioning away from it - more or less because we didn't have any option," he says.

Geothermal power is another option for businesses needed to shift off gas - but it can be expensive. Photo: Roy Taoho

The business has looked seriously at geothermal paired with heat pumps. The numbers were "insane".

"The capital required was absolutely mind-blowing," Simpson says. "And with electricity prices going up as well, the running costs were going to be the same, or more. You're kind of between a rock and a hard place."

With clear signals and a runway, he says, they could have plotted a path.

"Ten years would have been a lot. If there'd been a clear signal: 'By this date, you won't be able to run on gas,' we could have planned. Instead it feels like gas prices have just exploded with little to no warning."

Without support, many growers and manufacturers, he says, are simply absorbing the costs, passing some on to consumers and hoping something changes.

"Ultimately, if New Zealand businesses have been backed into this corner, to stay productive and operating we're going to need some help to transition," he says. "It's all good and well to say you've got to transition. But if the capital outlay is going to kill half the businesses in the country - and the gas prices kill the other half - what are we going to be left with?"

No silver bullets here

New Zealand's exit from gas was meant to be more orderly than this.

Under the previous government, officials had started work on a Gas Transition Plan, consulting on how to phase down gas while keeping the lights on. The idea was to map out which uses should be prioritised, when new supply would taper off, and how to avoid simply swapping gas for coal when shortages hit.

Alongside it, the GIDI fund helped pay for the hardware needed to switch: electric boilers, high-temperature heat pumps, biomass boilers, and efficiency upgrades in factories, schools and hospitals.

GIDI funded the switch from old coal and gas boilers to electric. Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

The goal was not only to reduce dependence on a fuel in decline - it was to cut emissions. Gas is one of the biggest sources of industrial climate pollution, and GIDI was designed to help firms shift, to help meet our climate goals.

That has now flipped: decarbonisation has become the bonus, with the driver keeping businesses running as supply worsens.

That dual purpose - climate and energy security - is what a "managed transition" was meant to balance.

The current government parked that process. It had its own plan: the idea of "market-led" transition: where the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and price signals will, over time, make fossil fuels too expensive and clean alternatives more attractive. Ministers have argued that public subsidies distort markets, and say a market-led transition will deliver lower costs over time.

The problem is, since they made that decision none of the markets involved have been behaving the way textbooks say they should.

Gas prices for industry have already doubled on average over five years, but new supply is still shrinking and exploration is yet to restart. At the same time, electricity prices are historically high, and security margins are tightening as gas-fired stations age and new renewables lag demand.

Further, the ETS carbon price has slumped, with multiple auctions failing to clear, weakening the incentive to invest in lower-emissions technology.

"There's enough evidence already to show that the market is demonstrably not working," Optima energy consultant Martin Gummer says. "If the market was right, then as prices have gone up there'd be more gas coming on stream. The opposite is happening."

In that context, a "market-led" transition risks becoming no transition at all.

And as a result, the country faces the worst of both worlds: emissions stay high while businesses face shortages and huge energy bills.

'The bottom has fallen out of the gas market'

The scale of what might yet happen if New Zealand can not get its energy crisis under control was laid out last month in "Energy to Grow", a report by Boston Consulting Group for the four main gentailers.

Some of the facts are now well-trodden: New Zealand's gas supply has fallen around 45 percent in six years. Domestic production now sits below underlying demand. But BCG did future projections too, finding the gas gap is set to worsen rapidly. In one scenario, demand exceeds available gas by roughly 10 petajoules (PJ) in 2026, and double that in 2027.

New Zealand's gas fields are in a state of decline. Photo: RNZ / Robin Martin

Even if big users such as Methanex and Ballance curtail production or exit entirely by 2027, their 28 PJ of demand is not enough to restore balance later in the decade. The market is still short.

In a dry year, the picture is worse. Gas-fired power stations need more fuel to back up hydro lakes, soaking up any spare supply that might otherwise go to industry. BCG warns that without better planning, "industrial demand destruction" - companies shutting or relocating because they can't secure fuel - could begin as early as 2026.

Earlier advice to ministers from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) and the Electricity Authority (EA) underlines how tight it has become. In July, officials were asked by Resources Minister Shane Jones whether New Zealand could burn more coal at Huntly so gas could be diverted to struggling factories.

On paper, yes: Huntly can run more on coal. In practice, both agencies say, doing so would push up power prices and increase the risk of shortages, especially in a dry winter. The "spare" coal units at Huntly are not spare at all; they are the emergency reserve that keeps the system stable when lakes are low or gas plants fail.

In other words - any extra gas for industry has to come from somewhere else.

"This is a serious and complex problem," Gummer says. "You can't just pull one lever and think it will be a silver bullet. The government has to pull all the levers it possibly can."

Fear of the unknown: Businesses don't know when, or how to jump

For many businesses, the result of the gas shortage has been a state of paralysis.

In a survey of 66 industrial gas users earlier this year, consultancy Optima found strong concern about future availability and pricing, with "low ability to transition in the short term". Twenty-five percent of respondents had already raised prices to pass on fuel costs; 14 percent had reduced production; eight percent had cut staff.

Of 55 firms, 28 believed they could fully or partly replace their gas use within about three years - but only with help on consents and capital. Together, they could cut demand by about 4.8 PJ a year. The combined capital bill was estimated at $532 million; most said some co-funding would be needed to make the numbers stack up.

Burning more coal at Huntly wasn't a viable alternative to gas, officials said. Photo: GENESIS ENERGY

The remaining 23 businesses said they could not get off gas within five years and needed a longer runway of up to 15 years.

The Energy Efficiency & Conservation Authority (EECA) commissioned qualitative research with 25 small and medium gas users - coffee roasters, brewers, pet-food makers, plastics moulders, hothouse growers and others.

It found many run specialist equipment with no cheap, like-for-like electric alternative.

Transitioning often means ripping out perfectly functional gas technology, investing heavily in heat pumps or biomass boilers, and in many cases - like at Rainbow Park - paying for expensive grid upgrades just to get enough power to their site.

The single biggest barrier those businesses identified was uncertainty: about how long gas will be available, if there will be rationing, how high prices will go, whether exploration will restart, whether a promised investment into LNG will arrive, and what happens if they jump early and the government later props the gas market up.

"We never considered the risk to the business of not actually having natural gas," one participant said. "We always expect that the price could fluctuate… But we never anticipated maybe having no gas coming from the pipeline."

"What is the priority of the gas supply going to be?" another asked. "If supply is limited, which it already is, how is energy going to be allocated? Who gets it first? Who gets it last?"

EECA chief executive Dr Marcos Pelenur says many firms feel they are being pushed into "make-or-break decisions": absorb higher costs, invest millions in new plant, or close.

"Gas has declined much faster than most people expected," he says.

Crucially, however, he does not expect a return to "the good old days".

"I think it is very likely that we will not have cheap, abundant gas," Pelenur says. "There are businesses out there hoping gas prices will go back to what they were ten years ago. I do not think that's going to happen."

EECA says businesses shouldn't be hanging on to the idea gas will be as cheap as it once was - the future lies in renewable electricity. Photo:

It is far more likely that the nation will have abundant renewable energy instead, Pelenur says.

His message is that businesses should act now on efficiency - EECA's walk-through assessments often find 10-30 percent savings - and start planning fuel switches, even if the big projects will take years.

But without a national strategy or substantial funding, that planning sits largely on individual firms: and eventually comes back to the issue of money.

The devil and the deep blue sea

For many manufacturers, the choice is not between cheap gas and slightly dearer electricity. It is between paying hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars to replace perfectly functional gas equipment - or taking their chances and hoping the fuel keeps coming.

"Most businesses are caught between the devil and the deep blue sea," Gummer says - unable to afford the capital cost of transition, yet unable to rely on increasingly volatile and uncertain gas supply.

"It's painful," one business owner told EECA's researchers. "The economics don't work out on our current return on investment."

Some talked seriously about shutting rather than transitioning. Others said they are passing costs on to customers, but worry those customers will simply go offshore - a wider risk of deindustrialisation.

Major employers such as pulp and paper mills, wood processors and food plants are deeply woven into local economies. If they close, the knock-on effects hit ports, trucking firms, engineering workshops, schools and shops. Once those jobs are gone, they are hard to replace.

Green Building Council chief executive Andrew Eagles says leaving it to the market is an unnecessary risk.

"You've either got a considered transition or a disruptive one that will damage people's lives - kids leave schools, people move towns, regional economies shrink," he says. "This isn't about abstract ideas - it's real people's lives."

BCG estimates that once big users like Methanex and Ballance have exited, every petajoule of additional gas demand destruction hits GDP harder and harder - about $400m for the first PJ, up to $700m for the tenth. Losing 5 PJ could wipe out around $3b of GDP a year; 10 PJ, around $7.3b, or nearly two percent of total GDP.

Replacing the gas system at Rainbow Park cost more than $2 million - around $800,000 of that came from EECA. Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

By contrast, the report suggests that with about $200m of co-funding, New Zealand could displace 10-20 PJ of industrial gas use over the next decade by helping firms switch to electricity and biomass.

"$200 million is a one-off," Hobbs says. "The cost of not managing the transition is in the billions every year. The benefits to the economy outweigh the costs by quite some margin."

Effectively, they're arguing to restart some form of GIDI, which co-funded dozens of projects at an effective support level of around $1.10 per gigajoule saved spread over 15 years.

RNZ asked Energy Minister Simon Watts whether the Government would consider supporting businesses with some kind of transition grant. Watts said he was "aware of the challenges" industrial gas users have been facing with increased costs and difficulties securing contracts", and outlined several initiatives underway.

The most significant is the procurement process for a liquefied natural gas import terminal, which the minister says is intended to bolster security of supply in dry years, support electricity generation during peak periods, and "potentially act as a fuel source for industrial users".

Alongside exploration incentives, the minister said work was underway to "remove barriers" to growing biogas and biomass as alternative fuels.

Energy Minister Simon Watts says he is aware of the challenges for businesses but would not pledge direct support. Photo: RNZ/Mark Papalii

Watts also highlighted broader financing tools that businesses could access - such as bank sustainability loans - and said the Government was working to "de-risk investment in thermal fuel and capacity", including by improving transparency in the gas market. He did not directly address further questions about demand-side support.

The path ahead

The analysts argue New Zealand does not have to chart such a difficult path.

Other countries facing gas shortages have taken a more deliberate approach both for businesses and in residential areas. When the gas crisis hit in Europe during the Russia-Ukraine war, there was a rapid push on energy efficiency, leading to major technological leaps.

In Victoria, Australia, where about 60 percent of homes use gas, the state government has moved to stop new gas connections in subdivisions and require electric hot-water heat pumps when systems are replaced.

But New Zealand has no equivalent national framework to either stop new demand locking into a fuel that is already running out, or managing the current demand.

Heat pumps can replace fossil fuel in many instances - including at high temperatures. Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

Instead, the government has only intervened on the supply side - investigating LNG imports and putting money on the table to extend gas drilling - while demand-side tools have stalled.

"If the government is prepared to look at co-funding LNG and more drilling, they should be prepared to look at co-funding transition for industry," Gummer says. "You need several strategies - that's how you disperse risk."

The experts are clear: the transition is coming any way you look at it.

They say the argument is not about pipes and boilers, or heat pumps and hot water. It is about who carries the costs and risks of an inevitable shift away from fossil fuels.

For Rainbow Park, an early grant and willing partnership from lines companies and power providers turned a looming risk into a triumph of innovation.

For Whakatāne Growers, and dozens of other firms trying to read the tea leaves, the story is very different.

"It's pretty daunting," Simpson says. "You're always thinking about it. Always working on it at home. But without some certainty, there's not much point making big investments - you don't know what the right thing to invest in is, or when the right time is."

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.