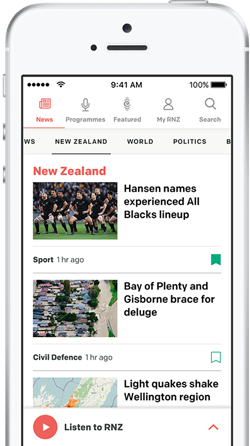

Photo: William Ray/RNZ

The mud slips below my boots as I slide down the slope. I grab a root to keep myself from tumbling down the steep, bush-clad gully.

Ahead of me, a small crew of seasoned ecologists and kaitiaki have their heads down, shaping rolls of wire mesh into a cage around a fallen ponga.

They are on a mission - trying to save a bizarre parasite thought to have gone extinct in the Wellington region more than a hundred years earlier: Te pua o Te Rēinga - "the flower of the underworld".

But this parasite has a vital role to play - it's a "tree on tap" - a way for native animals to draw sustenance right at a time and place when they need it most.

Follow Our Changing World on Apple, Spotify, iHeartRadio or wherever you listen to your podcasts

Te pua o Te Rēinga, Dactylanthus taylorii, lives entirely underground, with no leaves or chlorophyll to photosynthesise, instead it draw nutrients from the roots of a host tree. The plant only reveals itself briefly in the Autumn when its knobbly tubers push clusters of pink and purple flowers up through the leaf litter, providing a feast of nectar for native creatures, including its main pollinator, the short-tailed bat.

However, these flowers are also incredibly tempting to introduced pests like possums, rats, mice and pigs - which devour not just the nectar but also the flowers. This prevents the plants from reproducing and has driven them to the brink of extinction in most parts of mainland Aotearoa.

A short-tailed bat enjoying nectar-rich Dactylanthus flowers. Dactylanthus is the only chiropterophilous geoflorous plant in New Zealand. In plain English that's a bat-pollinated ground-flowering plant. Photo: Nga Manu Trust / David Mudge

Te pua o Te Rēinga were thought to be totally extinct in the Wellington region with the last plants being spotted in Kaitoke in 1914.Then, in late 2024, Nikki McArthur, a contractor for Greater Wellington Regional Council, stumbled across the species while conducting a bird monitoring survey in the Wainuiomata Water Collection Area - an area of forest which has been protected from farming and logging since the 19th century in order to provide safe drinking water.

"I was having a bit of an average day that day," Nikki remembers. "I'd sort of been huffing and puffing up the hill and was feeling a bit tired and a bit jaded and, yeah then looked down and saw these plants and it was just this complete turnaround of my day. It went from being a sort of a fairly average, kind of a physically demanding day at work to being just on cloud nine."

The discovery caused a stir among local conservationists, but also concern. The few surviving plants were in bad shape. It looked like they may have been rediscovered just in time to go extinct again.

Bart Cox, Barrett Pistoll and Graeme Atkins in Wainuiomata forest Photo: William Ray

By August 2025, the regional council assembled a small expedition to protect what remained, including Graeme Atkins (Ngāti Porou, Rongomaiwahine), an award-winning conservationist who has spent decades studying the species.

Our guide is Barrett Pistoll, Senior Environmental Monitoring Officer at the Greater Wellington Regional Council, who explains the history of the forest where the plants have been found.

"It's been locked up with water storage since I think the late 1800s, early 1900s, because there was a cholera outbreak in Wellington. So after that they looked further afield and they found this catchment; it's been locked up ever since."

"Thank goodness for that!" Graeme Atkins exclaims. "Whatever the reason, because it would be all covered with gorse if it had been cut down."

Instead, the old growth forest has remained mostly intact and inadvertently acted as a refuge for te pua o Te Rēinga.

When we finally arrive at the site, Graeme Atkins acts as our hype man.

"Drum roll, drum roll. I don't want anyone fainting now," he laughs. "Going to be the greatest moment in your life."

I'm not in much danger of fainting, to my untrained eye, the site looks like nothing more than a jumble of mossy, rotting logs "you really have to know what you are looking for," I say.

Barrett grins. "It really is a cryptic plant. Some people get their eye in better than others."

Beneath a fallen ponga, several clusters of tubers cling to life. "They all build on top of each other," says Barrett. "A big conglomerate of wartiness," Graeme adds with a chuckle.

Barett Pistoll places a wire cage, in the hopes that this will protect the plant from browsing invasive predators, as Bart Cox watches on. Photo: William Ray

As feared, most of the plants are dead or rotting, but not all of them. "A little bit of life in that one," Graeme says, crouching to inspect them more closely. The team begins cutting and shaping sections of wire mesh into cages - tight enough to keep possums out, but open enough for bats to slip through, should any still live in the area.

As the work continues, Graeme Atkins explains how his fascination with te pua o Te Rēinga began 30 years ago on the East Cape. "There was a known population up there on private land, and the department [of conservation] funded a project to learn what it takes to keep it around. I was lucky enough to be the project manager, the only one, actually."

Finding these "cryptic" plants wasn't easy. "Needle-in-a-haystack," he recalls. "With volunteers, they quickly run out of enthusiasm." The breakthrough came when he noticed possum droppings turning pink and purple during autumn. "I wondered why that was. So I started trapping possums and cutting them open. So when they eat the flowers off these plants it dyes their stomach and the contents that pinky purple colour. So it's a powerful presence/absence tool. Using the possums."

The tell-tale "positive possums" allowed Graeme to locate thousands of plants. "That was good and bad," he says. "Good because we found a technique. Bad because the department said, 'Oh, there's heaps of them, we don't have to worry.'" Graeme says that as soon as pest control stopped, the plants declined.

Dactylanthus taylorii in flower. Photo: John Hobbs

Introduced pests don't actually kill te pua o Te Rēinga, but they do eat the nectar-rich flowers before they can set seed, preventing the plants from reproducing. Looking at the site, Graeme says the plants have likely been here for decades. "What we've got here are old plants with very little recruitment".

Graeme believes the species once played a vital role in our forests. It's something he's seen first hand on Hauturu/Little Barrier Island, where both the plant and their pollinators have been allowed to thrive without the pressure of introduced pests.

"The Dactylanthus has just spread everywhere," he says. "It's like walking around on a wooden floor because all these rhizomes have just sort of welded together and I was lucky enough to be out there during the flowering season and so there were bats crawling all over the place to get at the flowers".

Te pua o Te Rēinga are prodigious producers of nectar and likely once a major ecosystem driver - given that they bloom at a time of year when there is little other food available.

"There must have been millions of these plants once upon a time," he says. "Millions everywhere. And that flow of nectar, I don't think it was just solely for bats … So many birds, insects, lizards would have made use of that resource. And so what we're dealing with now is just little glimpse on the mainland of New Zealand, where places like Little Barrier show you what it must have been like once upon a time."

Presuming this surviving population can be protected from pests, Graeme Atkins says there's no reason recovery couldn't happen in Wellington.

"A decent-sized plant could have up to 20 flowers, and each flower up to 200 seeds," he says. "So in no time flat, you can get a seed bank started."

As the last cage is secured, Graeme sums up what's at stake. "Like most of our threatened plants, this species is forever dependent on us now. Rats, possums, pigs - they're here forever. If we do nothing about them, these plants will go. It's as simple as that."

Sign up to the Our Changing World monthly newsletter for episode backstories, science analysis and more.