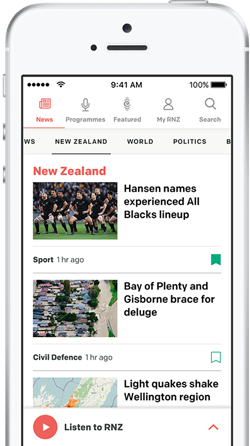

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

A major three-year study has found Māori are being undercounted in prisons by around six percent, masking the true scale of incarceration and its impact on whānau.

The kaupapa Māori research project, TIAKI, examined the experiences of whānau entering and leaving prisons, combining national administrative data with interviews led by researchers with lived experience of incarceration.

Researchers at University of Otago, Wellington - Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka, Pōneke have completed two studies within the project.

The first found primary care services were not meeting the high health needs of Māori recently released from prison, with cost a major barrier.

The second found Māori were undercounted by around 405 people in prison data because Corrections was not following national ethnicity recording protocols.

Lead author Associate Professor Paula King (Te Aupōuri, Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whātua, Waikato-Tainui, Ngāti Maniapoto) said the undercount affected resource allocation and government policy decisions.

She also criticised the state for failing to monitor the health and wellbeing of Māori both in prison and after release.

"What we expect is state accountability for state harms."

Māori undercounted in prison

King said the team was guided by kairangahau (researchers) with lived experience of prison to investigate ethnicity data, building on long-standing concerns about Māori undercounting across official datasets.

Corrections' recording did not align with Stats NZ standards, she said.

"People just aren't statistics - these are whānau with tamariki, with communities. If you're invisibilising Māori, you can't monitor Crown actions or inactions, or accurately assess the impact of policies," she told RNZ.

Māori were overrepresented at every stage of the criminal justice system: 37 percent of people proceeded against by police, 45 percent of people convicted, and more than half of the prison population at 52 percent - despite Māori making up only 17.8 percent of the population, according to Stats NZ data.

In women's prisons, the proportion rose to 61-63 percent, King said, and would be even higher when undercounting was considered.

Photo: RNZ / Blessen Tom

King said the undercount meant governments have underestimated how legislation affected Māori, including recent changes such as the Sentencing Reinstating Three Strikes Amendment Act 2025.

"The government's got a directive to put more people in prison and for longer... the numbers are increasing."

A Corrections spokesperson told RNZ ethnicity data was based on what prisoners self-report at reception, and people were encouraged to list multiple ethnicities, ranking them by preference.

"Corrections has proactively released data on the prison population, including breakdowns by lead offence, age and ethnicity dating back to 2009. Given how we present this on our website, for ease of understanding we have typically reported on what prisoners have self-reported as their primary ethnicity."

The spokesperson said Corrections was always seeking to improve its collection and proactive reporting of data, and would begin publishing more detailed tables that reflected multiple ethnicities from early next year.

Data provided to RNZ shows that as at 30 November, 2025, Māori made up 52.3 percent of prisoners using primary ethnicity, and 56 percent when all reported ethnicities were counted.

"Both measures demonstrate Māori are overrepresented in the prison population," the spokesperson said.

They said Corrections was committed to improving outcomes with and for Māori, "addressing the overrepresentation of Māori in the corrections system, and reducing reoffending".

Racialised inequities across the system

King said the research reaffirmed long-standing inequities across policing, charging, prosecution, and sentencing.

"It's longstanding - who the police choose to surveil, who gets charged, who is prosecuted, who gets longer sentences. These inequities are why the numbers of Māori in prison are so high."

Those released from prison had three times the mortality rate of the general population, with the first month after release most dangerous.

Early deaths were linked to chronic conditions, suicide, alcohol poisoning, injuries, and traumatic brain injury. Mortality was worse for wāhine Māori.

The study found that only 76 percent of Māori released were enrolled with a Primary Health Organisation (PHO), leaving a quarter without access to subsidised care.

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

King said rules excluding people in prison from PHO enrolment drive that gap.

"Services aren't meeting the high health needs of people released from prison… Māori providers are picking up the slack but are under-resourced and under-funded."

A Ministry of Health spokesperson told RNZ they acknowledged the findings showing Māori recently released from prison have poorer health outcomes.

"We note the finding that around three quarters (76 percent) of Māori released from prison were enrolled with a general practice in the 12 months following their release. While most of this group are therefore engaged with a primary care provider, we recognise this level of enrolment is lower than for other population groups."

They said enrolment was suspended during imprisonment because Corrections operated its own health services under a separate and exclusive funding agreement.

The ministry also said it has discussed prisoner enrolment settings with the Department of Corrections but while this work was underway, had no further comment.

Whānau-led solutions

Through interviews, whānau shared what would help after release: secure housing, employment or training pathways, culturally grounded programmes, and sustained whanaungatanga-based support.

"None of it is rocket science," King said.

"People want to be well, and they want their whānau to be well… They talked about identity, culture, mentors, having someone walk alongside them, and programmes that prepare people for release rather than focusing on deficits."

She said Māori providers already offered much of this support but have been underfunded for decades.

"If the highest proportion of people in prison are Māori, then why aren't kaupapa Māori providers being commissioned to support re-entry? What is funded is overwhelmingly mainstream."

Research Associate Professor Paula King (Te Aupōuri, Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whātua, Waikato-Tainui, Ngāti Maniapoto) hopes the research supports long-term system change. Photo: Supplied / Paula King

Immediate steps the government could take included: removing PHO (Primary Health Organisations) exclusions, following standard ethnicity data protocols and integrating health and disability services across agencies so people did not fall through the gaps, King said.

"At the moment everything is siloed. Someone goes in with health needs, there's no connection to their community care, and when they come out there's nothing.

"Under Te Tiriti o Waitangi, [the Ministry of] Health has obligations to ensure Māori can access services and be transparent about their decisions."

King hoped the research would support long-term system change.

"We're trying to break cycles of harm for future generations, to create a world our mokopuna can live well in."

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.